It’s been a while since I’ve written an article on a banned book, and since then I’ve added quite a few subscribers. If you’re new here, welcome. This is Book Burn, the portion of my newsletter where I share stats and thoughts on a banned book. Today’s feature is Lolita. If you’re unfamiliar, buckle up. Today’s subject is a doozy.

Note: There will be spoilers. Seeing as the book was published in 1955, this really shouldn’t be an issue. But if you don’t want to know what happens, please don’t continue. Read it and come back later :)

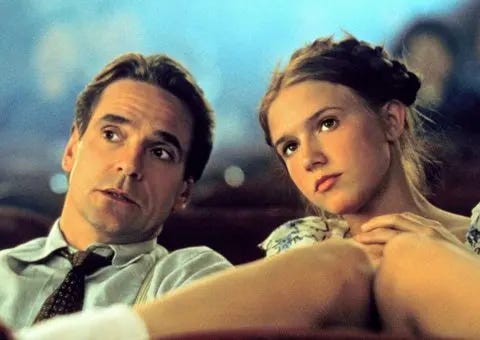

The term banned seems like an undershot when it comes to this piece. Lolita is probably the most controversial piece of literature published in the 20th century. Why, pray tell? Well dear readers, as is usually the case, it comes down to the sexual aspect of the book, but in this case, our narrator is a pedophile, the mentally unstable genius, Humbert Humbert.

The Stats.

It wasn’t just Americans who were up in arms over this book. Today, I offer you a brief international timeline of book bannings of Lolita.

France, from 1956-1959, Lolita is banned as obscene.

England, from 1955-1959

Argentina in 1959

New Zealand in 1960

That list is not comprehensive. Canada and South Africa banned it as well. And when the book was published in the United States (a surprising fact given our current state of affairs), the worldwide censorship brought instantaneous publicity. Of course, since then, the book has been challenged repeatedly all across the United States. The reasons? Let me tell you about the book. I’m sure you’ll see why.

The Story.

Our story begins in a prison, where Humbert Humbert is awaiting trial for murder. He writes a confession, pouring his soul into a memoir detailing his dark and twisted proclivities. He is sexually attracted to children, girl children, whom he refers to as nymphets. Not only that, he has acted on his attraction, going so far as to marry a woman to sexually possess her 12-year-old daughter, Lolita.

“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.”

That sentence out of context reads like an impassioned Shakespearean declaration of love. You can imagine star crossed lovers, fated for tragedy with that line. Avid readers will know how this one goes. But the next line breaks the mold. Turns your stomach.

“She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.”

Humbert Humbert was 37 when he met little Lolita. A European who immigrated to the U.S. following a failed marriage to an adult woman, he takes up residence in Ramsdale, in the house of the widow Charlotte Haze, Lolita’s mother. This is after multiple stays at a psychiatric hospital and an expedition to arctic Canada, where he finds that he is not attracted to the children.

“Nymphets do not occur in polar regions.”

Charlotte falls in love with Humbert, and in a desperate attempt to stay close to the young Delores, he feigns affection, proposing after she gives an ultimatum: leave the house, or tell me that you feel the same.

His lust towards the young girl grows, culminating in a plan he undertakes to drug both Charlotte and Lo in order to do whatever he pleases with the girl without her knowledge. He reasons that no one will be hurt that way, and details all his plans and thoughts in a diary that he locks in his desk to keep anyone from finding out his intentions.

Of course, the plan fails. He is only married a few months before Charlotte discovers his diary. She is disgusted. Outraged. Even as he tries to assure her that what she is reading is merely fiction, research for a novel and nothing more, she knows better. She storms out of the house after a fiery confrontation to send out letters detailing Humbert’s true nature. As she crosses the road, blinded by hurt and fury, she is hit by a car and dies.

Which leaves the villain Humbert Humbert with Lolita.

Lolita is at a summer camp when it happens, and Humbert is left with the job of telling her about her mother’s passing. He picks her up from Camp Q, and decides to check into a hotel before he breaks the news. The following day Humbert details his first sexual encounter with the child, stating:

“It was she who seduced me.”

The line shakes you, but it isn’t surprising. Humbert has been detailing Lolita’s flagrant flirtations throughout their time together, first as roommates, and then as step-father and step-daughter. She behaves beyond her years. It’s easy as a reader to see something there and think that there was something mutual in the exchange.

Of course that’s how Humbert would want us to see things isn’t it? The genius of Nabokov’s writing is that you see things from his point of view, “She seduced me,” with little quotes from Lolita like, “…wouldn’t mother be absolutely mad if she found out we were lovers?” Stolen kisses on the stairs and hand holding in the garden.

But to read that is to miss the details. Not only that, to believe the description is to trust the criminal telling the story. After that first sexual encounter, which Humbert believes was a willful act on her part, Lolita demands to call her mother, even threatens him with police. She calls him a brute and tells him he hurt her. Can the point of view of the pedophile really be trusted here? No. He is an unreliable narrator to the core. He sees Lolita’s child actions as flirtations, the signs of her premature sexual experiences as a license to take advantage of her. He justifies it.

They embark on a road trip across the United States.

Here, the book details what amount to an endless slew of motel rooms, sexual encounters, Lolita’s boredom and desire for normal childhood experiences, and ultimately, Humbert’s drive to control and user her at will. The book is tragic, disgusting. The language is beautiful, magnificent.

Take the age difference away, and you would have a real love story. A tragedy unfolding before our very eyes. But Nabokov heaps tragedy upon tragedy. It is forbidden love, but not because of feuding families or an arranged marriage: because Humbert is a monster, and Lolita is his prey.

“We had been everywhere. We had really seen nothing. And I catch myself thinking today that our long journey had only defiled with a sinuous trail of slime the lovely, trustful, dreamy, enormous country that by then, in retrospect, was no more to us than a collection of dog-eared maps, ruined tour books, old tires, and her sobs in the night — every night, every night — the moment I feigned sleep.”

Even as he watches Lolita’s mental and emotional health deteriorate, he demands sexual favors for even the most basic of requests. She is an orphan trapped by a predator. Life circumstances have worked so completely against her and in favor of the villain. Her life is a nightmare scenario for any young girl. No mother to protect her. No outside eyes to notice the hellish lifestyle she is being subjected to. She is completely alone.

In the end

Humbert Humbert loses Lo after a visit to the hospital. They are on their second road tour of the United States, a jealous decision made in reaction to Lolita making friends at a new school and desiring time with peers. When she falls ill, Humbert takes her to the hospital. When he returns, a nurse informs him she has been picked up by her uncle.

He rages, searches for her, but in the end, he can’t find her. His life goes on, the color drained by the loss of Lolita. He returns to the psych ward as he fears a loss of touch with reality. He lectures at colleges. He meets a woman and lives with her. He doesn’t hear from Lolita again until three years later, when she is seventeen years old. She is married to a mechanic, expecting her first child, and needs money. She writes to Humbert and calls him dad.

He visits her, mourns the woman’s body that has bloomed from the child he loved and still loves. He wants to take her away, pay for a house, help her raise the child. If it is a girl, he fantasizes about having another nymphet, one in the likeness of her mother. The line of makeshift incest and abuse can continue on and on. That is how demented he is.

“I looked and looked at her, and I knew, as clearly as I know that I will die, that I loved her more than anything I had ever seen or imagined on earth. She was only the dead-leaf echo of the nymphet from long ago - but I loved her, this Lolita, pale and polluted and big with another man's child. She could fade and wither - I didn't care. I would still go mad with tenderness at the mere sight of her face.”

When Lolita refuses, he asks her to tell him what happened at the hospital. Who took her? It was Clare Quilty, a playwright and pedophile who took a liking to young Lo for the same reasons Humbert did. He was a family friend, a successful writer, wealthy and a deviant. He produced child pornography and made demands for those in his circle to appear in films.

Lolita runs into him on the road, and sees a way to escape Humbert. She leaves one abuser for another, a tale unfortunately as old as time. When she refuses to take part in any of the sexual acts because of her love and devotion to him, he kicks her out. Humbert leaves after finding out this news broken hearted, disgusted at the way Quilty treated Lo. He makes his way to kill him.

“He broke my heart. You merely broke my life.”

Wow.

Isn’t it amazing to read the risks that writers and publishers take? (And where has that spirit gone? Is it out there? Anybody?) I have friends and acquaintances who are unsure about whether they should include a character of a different race for fears of misrepresentation. And while that sensitivity is valid, in so much as you want to get a character right, it floors me to think about the kind of guts it would take to write from the perspective of a pedophile.

Nabokov paid a price of course, but he was also made famous through Lolita. Still, I have to confess that as I read it, I questioned his own inner life. Were these the secret confessions of a real life pedophile? The writings of a man who can weave words so beautifully that you forget he is writing about a child? There is no evidence from his life that would lead me to that conclusion. But of course, it bubbles up.

What a heavy burden to bear. He must have known what would come of his book. His son was routinely asked how he felt being the child of a dirty old man, and his book has been thrown out as pornographic trash by entire countries. Nabokov’s response to the question we all want to know: why write about this topic?

For the sake of form. He wanted a problem that was difficult to solve. That was his motivator in writing period. To take a puzzle, something that shouldn’t be able to be written about, and to solve it. To write forbidden love that does not make the reader pine, but throw the book in anger, call their representatives, burn the damn thing in the square. To write a forbidden love that breaks us. He was traveling the country with his wife researching butterflies across the United States when he wrote Lolita. The text was scribbled on index cards in motel rooms as he wove the tale of the depraved Humbert.

The language in the book is so astounding, the words so expertly woven together, that it shocked me to learn that Nabokov’s first language was Russian. He was trilingual, and also a synesthete who saw letters in different colors. Did that contribute to his incredible command of the English language? Maybe. Maybe he was just a genius. Take these lines.

“There are few physiques I loathe more than the heavy low-slung pelvis, thick calves and deplorable complexion of the average coed (in whom I see, maybe, the coffin of coarse female flesh within which my nymphets are buried alive).”

And this desperate paragraph.

“I recall certain moments, let us call them icebergs in paradise, when after having had my fill of her –after fabulous, insane exertions that left me limp and azure-barred–I would gather her in my arms with, at last, a mute moan of human tenderness (her skin glistening in the neon light coming from the paved court through the slits in the blind, her soot-black lashes matted, her grave gray eyes more vacant than ever–for all the world a little patient still in the confusion of a drug after a major operation)–and the tenderness would deepen to shame and despair, and I would lull and rock my lone light Lolita in my marble arms, and moan in her warm hair, and caress her at random and mutely ask her blessing, and at the peak of this human agonized selfless tenderness (with my soul actually hanging around her naked body and ready to repent), all at once, ironically, horribly, lust would swell again–and 'oh, no,' Lolita would say with a sigh to heaven, and the next moment the tenderness and the azure–all would be shattered.”

How do you write the taboo?

If you’ve followed any of the book ban meetings that have gone on within school boards and legislative halls, you’ll get a certain question: is this of educational importance? What separates literature from pornography?

“If you can’t read it aloud, then it shouldn’t be on a shelf.”

Is that really where we draw our lines in the sand? That’s one hundred percent individual. Have you listened to any comedian podcasts? They say the absolute most debased things, but it’s all for a laugh. I’m sure they’d have no problem reading actual pornography in a school board meeting. There’s got to be something of intention included in the discussion.

Is the point of the story arousal? If that is the point, is that pornographic?

There is a line, isn’t there? With storylines like Lolita’s, it can be a difficult delineation, particularly for more traditional people who want nothing but an allusion to the thing that happens in the dark of night behind closed doors, and sometimes not even that, and certainly never for pleasure and only in the context of procreation.

For them, the book will be a non-starter. They won’t get anything out of it but the shock of sex being talked about in the open. For the language lover? The writer or reader who wants to master story and phrasing, the weaving of plot and the magic of writing about the taboo in a way that shocks without being pornographic? It’s a must.

I watched a Jack Ketchum interview a couple of months ago. I had just finished The Girl Next Door, and was struggling to make sense of the complexity of my feelings around the subject. The book details severe child abuse in which the neighborhood children participate in torturing the niece of a neighbor. She is a teen girl, and the boys, even her own cousins, are attracted to her in the story.

That creates a weird dynamic doesn’t it? There’s obviously tension, sexual tension.

The author details the difficulty in keeping the story from becoming pornography, a trapeze act that isn’t for the faint of heart when you’re writing about a subject that isn’t just terrible, but is based on a true story where rape did occur. His solution? To give distance. He specifically decided to tell the story through the eyes of a neighbor boy to give space to the first-hand knowledge he has. If the boy was in the house, he would be privy to everything. Having him live next door gives enough range that some things can be implied.

“I tried to do it as graphically as I could without turning it into pornography. I knew I was skating a line there that was a very fine line, and I paid far more attention to that line than I’ve ever paid any attention to anything since. It was important to me that this be seen as a challenge almost to the reader. That if you turn the page, this is so extreme, that you’re culpable in the crime…and a lot of people did, and I’m glad they did. Because I think it’s a moral book…What I’m positing to the reader, is if you were there, would you have stopped it, or would you have been so titillated that you would have participated?”

-Dallas Wayr (pen name, Jack Ketchum)

What an interesting solution. In Lolita I noticed something similar. While Humbert Humbert details his fascination with Dolly’s shoes, her hair, her lengthy limbs and the color of her skin, it stops there. We don’t have intensely detailed descriptions of the sexual encounters, and there are many. Humbert’s most intense obsessions seem to be in her child habits. The untied shoelace, a bit of dirt on her face, her boredom and bad attitude on the road. It keeps the story in check and outside the realm of an FBI writeup on sexual deviance. It’s probably the reason that a publisher was willing to take the chance.

Lolita is also not a totally innocent child. I know, I know. But follow me on this train of thought before you bring the pitchforks. I am not saying she isn’t innocent as some kind of moral judgment. No. She has been sexually abused before Humbert ever came into the picture. She has experience. She acts the experience out again and again. That isn’t a flaw on her part. It’s a tragedy. In the end, she flees Humbert’s arms into the arms of an arguably worse (or at least evenly deviant) partner. And this one, she says she was in love with. Was crazy about even. And why? Because he was such fun.

Imagine if Nabokov had chosen to write her character as a fearful, shy girl, a victim once and then twice and then a third time of sexual abuse? She is that underneath, but on the exterior, in Humbert’s eyes, she is a knowledgeable, flirtatious, outgoing girl. He thinks she has some idea of what she’s doing, that she initiates it even. That is how he can so boldly proclaim that it was she who seduced him! It’s subtle, but hasn’t he distanced Lo from us, the reader? Made us question whether he really is all to blame after all. Of course, we should know better. It is the same tactic used by defenders when they ask a rape victim what she was wearing that night, whether she accepted a drink. Humbert would take that approach wouldn’t he? After all, he is writing to ladies and gentlemen of the jury.

Books like these, impossible books, are a question for us as a society. The same way Jack Ketchum posits his question in The Girl Next Door, Lolita asks us the same. People who come away from the story imagining her to be the reason, the catalyst for the tragedy that became her life, are likely the same ones who will ask Anita Hill why she minded being asked about her large breasts in her work place.

It’s not that we don’t believe the things written about in these books happen. Of course they do. But sometimes, I think books are banned because either the reader is so thrown off by the material that they don’t understand the questions being asked, or they don’t want the mirror held up. They don’t want to look inside and ask themselves what they would do, were they in the same position.

I get it. I don’t always want to either. As I’ve stated many times, I’m often the villain. But I’m always glad when I do.

You homed in on the crux of the issue with your very incisive exposition and analysis of the book in the second half of the post. The bit about writers today living in fear of exploring such themes and incorporating such characters in their work is key. That literary license is what makes fiction so powerful, because those challenging ideas expressed in a novel tear away the curtains of civility and social “normalcy” and ask questions we’re not allowed to ask in smart company for fear of being labeled mad or dangerous. I would argue that there’s much more to learn from an author’s potential “misrepresention” of a person or group than there is from preventing the author from ever running the risk of causing offense.

I think you've convinced me to read this. I skimmed a bit of the spoilers, but wow is that prose good.