Good morning.

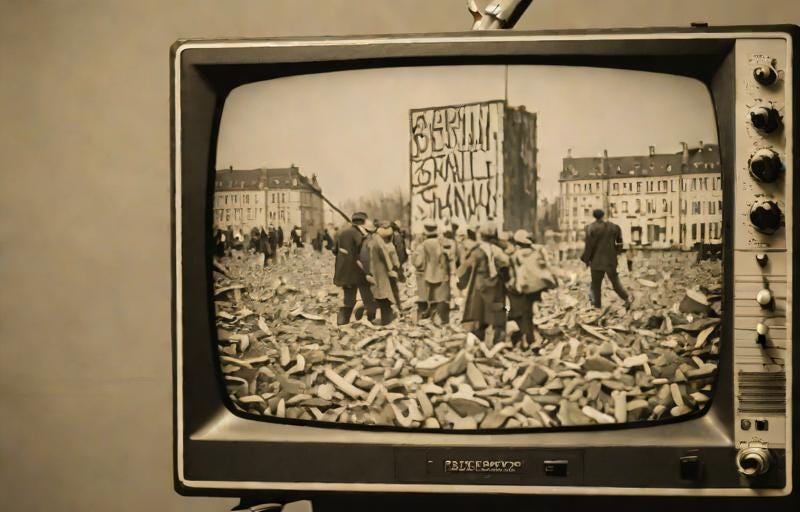

If you’re brand new to Kindling, this is Sleep Tight, where I share original short fiction. This one is a long time coming. I hope you enjoy it. It came out of some weird obsessive thought I had about TV glass. The question? What if it contained worlds and timelines? And what if some of it got inside of you, and those worlds played out in your head and your ears until it drove you crazy? What if it forced you to be a prophet?

If you read Flat Tire, Over, you’ll see the similarities there. I explored it in a flurry of short stories until it stopped cropping up. In Flat Tire, it’s one blip in the plot, zoomed out. In this one, it’s everything.

Enjoy!

Used to be when you would watch TV, there were only a few channels, and when you changed it to channel three or five, there wasn’t a remote. In my house, the kids sat on the floor, got up when their parents told them to put on the evening news, or turn the volume up or down. The programs didn’t go too late, and if you woke up in the middle of the night with nothing to do? You were out of luck. The only thing on the screen were rainbow vertical stripes, pink and green and blue. It stayed that way until morning when the next show came on.

People slept better back then, had less to do once the sun went down. But there were other problems with the TV. No not all the sets mind you, but I know there was something wrong with at least one. Watched it unfold in my own neighborhood. If I tell you, you won’t believe it. But that’s something I can’t worry about anymore. I’ve got to tell someone. If I say it enough, maybe one of you will do something. Stop it from happening again.

***

I was sitting on the curb out in front of my house when I first met Jamie Lewis. He was tall for twelve and lanky. His parents dressed him sharp, in beautifully colored striped button downs and a brown leather belt that he wore everyday with long jeans, even in summer.

It was summer then, the best of it. Early June when school first lets out, and the crickets have just started singing. The sun was pleasant and warm on my back that day, and I was doing my daydreaming, happy but lonely.

I hadn’t seen him before. He had only moved in a week earlier. But he came bounding up to me, a friendly smile plastered across his face, basketball held firm between his hands. I wasn’t bullied, but I was quiet. Invisible to most. The attention from him, the gaze and the vibrant toothy grin threw me. I blushed and looked away, unsure of how to take his demeanor.

“Hey there,” he called. His voice was sure for a kid, confident and deeper than mine.

I managed a wave in his direction, but it was short and stiff. I tucked the same hand under my butt, sat on it to make sure I couldn’t do such a sloppy, stupid gesture again.

“What’s your name?”

“David,” I croaked out, still too quiet for him to hear.

“Huh?”

He leaned closer attempting to tune in and listen to my little voice squeak out a response. I cleared my throat, feigning phlegm that would explain why I hadn’t been able to say it quite right. He laughed a little.

“You play ball?”

He was standing in front of me when he asked, his shadow shading my eyes so I could look up at him. He pumped the ball out towards me gently, the motion itself a question. I shook my head. He breathed out big, like he had been holding his breath that whole time and plopped down next to me on the curb when I said so.

“Me neither,” he confessed, and I thought I detected a hint of shame.

“Why’d you ask then?”

“My dad wants me to.”

We both stared at his father. He was turned away from us in the garage, bent over the insides of a car engine. I understood about things like that. Once, my father had made me join the baseball team. It had been his game when he was young. He just knew it would be mine as well.

On the first pitch, my bat hit the ball hard, but the angle wasn’t right. It popped right back into my eye.

“Go on son! Try again!” My dad had yelled from the stands.

But I couldn’t stop crying. In the emergency room they said it had fractured my orbital socket. I could still picture the way he looked at me in the rearview on the drive home. I stared back at him with my one good eye. He didn’t say anything. Didn’t have to. I knew he was disappointed.

“What do you like to do?” I asked, changing the subject so he didn’t have to think about it anymore.

“You ever read comic books?” His eyes lit up, big and excited.

I shook my head no and the light left.

“My mom doesn’t like stuff like that,” I said.

He nodded like he was used to that answer, and we sat in silence for a while, me picking at a blade of grass growing in between the cracks of concrete, and him turning that basketball over in his hands again and again.

“You like to watch TV?” he finally cut in.

“Yeah,” I said, and I meant it.

“You wanna come over tonight? We can watch some.”

“I’ll have to ask my mom.”

“Okay.”

And then he was off.

“Hey, where you goin’?” I yelled to him, worried that I’d done something to make him leave so fast.

“I gotta eat lunch! I’m starving!”

He yelled it running backwards, the ball tucked expertly in the crook of his elbow. I never would have known that he didn’t like basketball. He looked like he was made for it. I had never been invited to a neighbor kid’s house. Not without my mom making plans with a friend of hers, the kid whispering to his mother who would remind him of his manners, and tell him to show me his toys.

He turned back just before he went in the house, and did something crazy. He waved at me, like he was sorry that he had to go and eat. Sorry to miss out on talking on the curb. I couldn’t help it. I smiled and waved back.

***

Jamie knocked on my door just after dinner. My mother answered on purpose I knew. She wanted to get a read on him. He shook her hand and answered all her questions politely enough that she actually let me go. It was a funny thing about my mother. For all her trying to get me a friend, when I looked back I saw that her face looked drawn and sad, the usual cheerful demeanor diminished somehow by my leaving with him. Like if things were going to come together for me, she wanted it to be because of her.

It was years later, when I introduced her to my then girlfriend who would become my wife, that I finally put those pieces together. I had gone on a few blind dates she had set me up on. Daughters of friends and acquaintances. When none of them worked out and I brought Joanne home, her face looked the same. I didn’t understand it then. In the summer of 1964, it was just a feeling, vague and not yet carved, like a lump of clay before the sculptor sets it free.

As soon as the door shut behind us, we were off. The air on my skin was sweet, and the excitement I had was unparalleled. Sure, I was doing the thing I did nearly every night, my ass plopped on the floor, head craned towards the little square television. But now it was different. Now I had a friend.

When I walked through Jamie’s door, I walked into another world. The smell of dinner still hung heavy in the air. It was hot, and everything was decorated in hints of reds and vibrant purples. Even the couch was a Burnt Sienna.

“Far out,” I said, mimicking some musician I had seen on a variety show.

Jamie gave me a look, a smile spread cockeyed on his face.

“You act like you never seen a house before.”

“I haven’t.”

He looked at me again, this time the smile gone.

“What I mean is, not like this one.”

Jamie laughed again and waved me on into his room. For a minute there I thought the tide of our short friendship was going to turn, but I had saved myself.

The walls were covered in framed photographs, but unlike my home, they weren’t filled with family faces. They were machines of all types, his father standing next to some here and there. In one he was dressed in a white coat, shaking hands with another man whom he towered over, smiling from ear to ear. The other guy was bald, a few strands combed and pasted over his shining egg head. He was dressed in a white coat too. But there wasn’t a smile on his face.

“Come on,” Jamie said impatiently, but my eyes were fixed on the photographs.

“What are all of these?”

“All of what?” He looked at the wall as if for the first time, puzzled by whatever it was I saw there.

“These machines.”

“Oh, those,” he sounded bored. “My dad is an inventor.”

The thought was incredible to me. An inventor. I always knew they existed. We had learned about inventors in school. Tesla and Edison and George Washington Carver. On my own mind had been the Bomb. The Big One. That thing was on my mind ever since we started practicing the drills.

“Under your desks, head tucked, arm shields.”

That was the way Mrs. French taught us. A little sing-song quip to remind us what to do if the Bomb ever came our way. When we first learned it I was scared, but she made me feel better. She looked at me with those blue eyes and said that as long as I followed directions there was nothing to worry about.

It was my father who told me the truth. Only he didn’t tell it to me directly. I overheard him talking with my mother the night after I told him about it.

“Ain’t nothing can shield those little kids from an atomic bomb. It’s just a way for the government to keep people from panicking.”

I looked back over the photos, searching for some type of war machine, the dark hallway somehow growing darker. But these things, little automobiles and colored metal boxes with antennas sticking out didn’t seem so bad. Didn’t seem like they could kill someone anyway.

I finally followed Jamie, but my eyes stuck to the pictures. The last one I saw was of an ordinary television set. Two antennas stuck out the top. Peg legs supported the bottom, lifting it maybe six inches or so off the ground. The glass screen was slightly rounded, like it was coming out at you, a camera lens that fed you the pictures instead of the other way around.

“What’s this one?” I asked him.

He sighed and shrugged his shoulders impatiently.

“I guess it’s a TV.”

“He invented TV?”

“No stupid. ‘Course not.”

I kept looking. There wasn’t anything special about it from the photo. At least no that I could see.

“Stupid thing is in the living room. You’ll see it later.”

He walked on towards his bedroom.

“Jamie, does he call it anything?”

Another sigh came out long.

“He calls it The Tube. Now will you hurry up and get in here? I want to show you my stuff.”

To be continued…

Like it! This concludes our broadcast day...(cue Star Spangled Banner).

I am interested to find out what happens next. I can so relate to the setting having grown up in the 60's and 70's.