A quick note: Included in this article is a book review with spoilers. I’ll warn you before they hit, but some of the topics might veer into spoiler category. The book is The Last House on Needless Street, by Catriona Ward. I’ll give a quick summary, and if it looks like something you want to read, I’d advise you to do so before continuing. The story is of the twisty-turny variety, and I don’t want to take away that experience for any would-be readers.

Last month I discovered a new horror author, Catriona Ward.

I had never heard of her, but she came highly recommended (I believe on a podcast) so I bought the first book I saw, which happened to be The Last House on Needless Street. Like a lot of the books I read, I went in with no summary. I tend to be drawn to writing over plot, so a back cover glance doesn’t always do a lot for me. Even if a book doesn’t knock it out of the park for me plot-wise, I can hang and give an author a second or third chance if I see something in the characters.

Imagine my surprise when I hit the second chapter and found that one of the narrators is a cat. I’m not going to lie to you here. I wasn’t impressed by that. It’s imaginative, but it’s also a little weird to switch perspectives between the human man I had just been introduced to (Ted) and his pet cat (Olivia), but I held out because the descriptions from Olivia’s perspective were interesting, novel even. To avoid making my mistake, I’ll give you the Amazon synopsis. It’ll make you more likely to press forward if you’re like me and find yourself largely uninterested in cat perspectives in your horror novels.

Catriona Ward's The Last House on Needless Street is a shocking and immersive read perfect for fans of Gone Girl and The Haunting of Hill House.

In a boarded-up house on a dead-end street at the edge of the wild Washington woods lives a family of three.

A teenage girl who isn’t allowed outside, not after last time.

A man who drinks alone in front of his TV, trying to ignore the gaps in his memory.

And a house cat who loves napping and reading the Bible.

An unspeakable secret binds them together, but when a new neighbor moves in next door, what is buried out among the birch trees may come back to haunt them all.

There you go. That’s all you get with no spoilers.

I wasn’t going to do a write-up of the book. Not because it isn’t good—it is—but I tend not to do reviews or whatever you want to call them, unless they tie in to something in my inner world. Some bigger picture I’m mulling over. I never know why things string together in my mind, but Ward’s book came floating back today after I read the article below.1

It details the portrayal of people with mental illness in media and the general cultural discussion by those advocating normalizing mental health, as being off about the darker realities of living with mental illness. Not only off—that’s putting it too lightly—but dishonest, blatantly ignoring swaths of people’s experiences that are deemed too ugly for advocacy. Mills Baker writes his personal experience as an outcast in the 80’s, when Johnny Depp and Winona Ryder were making weird popular.

Despite the sudden attraction to being an outsider, he blows it out of the water with the spotlighted reality that the people being celebrated for being so weird were objectively attractive, cultural icons who appeared on the red carpet and magazine covers. They were talented, able to draw people in with that something that got them into show business to begin with.

Of course it’s worth noting that before Winona was famous, she was tortured in high school as detailed in this interview with Henry Alford.

Didn’t you get beaten up in seventh grade for dressing up like Jimmy Cagney?

I was wearing an old Salvation Army–shop boy’s suit. I had a hall pass, so I went to the [girls’] bathroom. I heard people saying, “Hey, faggot.” They slammed my head into a locker. I fell to the ground and they started to kick the shit out of me. I had to have stitches. The school kicked me out, not the bullies. Years later, I went to a coffee shop in Petaluma, and I ran into one of the girls who’d kicked me, and she said, “Winona, Winona, can I have your autograph?” and I said, “Do you remember me? I went to Kenilworth. Remember how, in seventh grade, you beat up that kid?” and she said, “Kind of,” and I said, “That was me. Go f— yourself!”

Still, we can all think of the people we went to school with who fell objectively into the category of unremarkable, unattractive, rejected and outside of the rest of the student body. Maybe we were them. Maybe we still are.

A kid who put hot dogs in his pocket and ate them, lint and all, comes to mind. Another who was so unstable, she randomly threatened to stab people with whatever school supplies were available at random: pencils, compasses, her nails. These weren’t quirky kids, would never play the cool artist in some teen romcom. They were un-relatable, disturbed, other.

When we compare those kids to the cool weirdos brought to life by the mind of Tim Burton, do they really compare? Christian Slater wasn’t covered in cystic acne in The Heathers. On the contrary, he represented the cool, smart, kick-ass alternative kid that we all kinda wanted to be. (Even if he was a psychopath).

What’s my point? That in the time when The Weirdo became celebrated in music and film, the lived reality of The Weirdo was not that. The characters portrayed on the screen and singing in 80’s music videos were a watered down version, their defects and ugliness stamped out until they were actually cool.

And now, Baker writes that the same thing is being done with mental illness.

In an effort to remove the stigma of talking about and getting treatment for mental illness, advocacy groups have whitewashed what is and isn’t mental illness. Take Kanye West’s somewhat recent public struggles, and the public reaction of some of those advocates to his antisemitic comments, summed up simply in, “This is not bipolar disorder.”

To which Baker, who has bipolar, replies with the following:

Motherfuckers, please! AsFreddie deBoerhas pleaded many times: stop pretending that mental illness doesn’t have real costs. Attempts to “reduce stigma” cannot involve falsifying the thing you wish to destigmatize; if they do, we are stigmatizing it even more! Bipolar people definitely say extremely fucked up shit sometimes.

I remember watching a clip of Kanye’s interview with Alex Jones, where he proudly proclaimed that he loved Hitler. My husband and I talked about it, how strange it was to watch a black man pay homage to a movement that would have wiped him out. At the end of the conversation I noted how weird it was that this was making headlines in a way that painted him as a sane Neo-Nazi.

“He’s not well,” was my final response.

I’m sure there are many people, maybe even my readers, who would see this as some kind of cop out. I mean it purely as a fact of being mentally unstable. To Mills’ point, that kind of instability is not tolerated, even by the communities seeking to advocate and normalize mental health issues. That begs the question: where is that person to go, when for example, the manic episode is over? I think they should be able to turn to art, and in my case, I’m talking about the written word. Walking that line in writing characters that don’t reinforce harmful stereotypes while still giving room for the real life variety of human expression in every way, good and bad, weighs on me often.

And that is where this article led me.

Not everyone knows about bipolar. I learned this recently in conversation with an acquaintance when the talk veered into anxiety, depression and medication. He didn’t believe that medication was necessary for anxiety because the people in his life seemed to need it forever after it was prescribed. In his mind, it was a crutch. My mind of course went to the people in my life who, unmedicated, cause real damage to their life. Sometimes it takes years to make up for it.

“Medication can be the right answer,” I said, and described some personal experiences.

It’s not the first time I’ve heard talk like that around mental health, and as someone who has family and friends with real mental health issues, ranging from generalized anxiety disorder to bipolar, I found it offensive. Anyone who has seen the struggle people go through would. No one asks to be the person with depression or schizophrenia, and no one needs the extra judgment about treatment for it.

But the reality is that there is ignorance around mental illness and what it is exactly. Its invisibility lends itself to all sorts of myth and legend, ranging from total denial of its existence to fascination that borders on worship. More than once, I’ve heard people advocate living unmedicated as the way to be a true artist, to tap into some hidden well of creativity. There might be some truth to that, but of course I’ve heard the same around addiction.

There is no one right answer, not just one reality about mental illness and its effect on people, except that it makes living life in a stable way difficult or impossible. Story is powerful for me, and in reading this article, I realized something strange. Despite knowing real life people with mental illness, even witnessing friends and family have psychotic breaks with reality, I still ate some of that media cool outcast bullshit up.

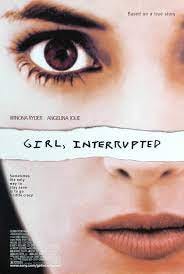

As a young person, I fell in love with Girl, Interrupted. The beautiful Winona Ryder and Angelina Jolie made it impossible not to. Sure, bipolar was a bump in her character’s life, but it was also rebellious, exciting, raw. She said bad things, did bad things, embarrassed her family. But it felt a little like Jim Morrison. Rock and roll baby.

Fast forward to my twenties, when a friend first started showing symptoms of bipolar. She stopped sleeping. Couldn’t, no matter what she did. Paranoia followed, the constant fear that the end times were coming (preached by the fundamentalist Christian church I belonged to at the time), and a certainty that when the time came for God’s judgment, she would be swept away with the wicked. The next year she lost her job, got put on sleep meds, underwent deliverance prayer sessions with pastors where they tried to cast demons out, and then spent nearly a year in bed with totally debilitating depression.

“I can’t even shower,” she said to me.

Then she seemed like she was getting better. Much better. She went into full blown mania, a rapid upswing. Strange messages on social media, a frantic drive from her parent’s back to our place, an early morning breakfast at a truck stop. The car when it parked, filled to the brim with piles of things. Clothing and boxes and purses, papers and journals and art supplies. Credit cards maxed out, a hundred dresses from Target, dangerous driving, talking and talking without pause in ways that didn’t make sense. All surrounding a grandiose and euphoric epiphany about her real purpose: to be an artist.

That trip ended with an arrest and a hospital stay where she was finally diagnosed with bipolar disorder. It wasn’t sexy. It was scary and painful, and to this day, terribly embarrassing for her.

I talked with a family member about it, trying to get some kind of tool, a snappy saying that I could come up with to deal with it. She had been diagnosed in her twenties, so I thought she would give me something relatable. I tried to make light of it, in my mind making the best of a hard situation, not wanting my friend to feel stigmatized or bad for something out of her control. I said something to the effect of, “Well you’ve made a life for yourself and you have it. I mean, is it really that bad of an illness?”

She told me that it was about the worst you could have, besides maybe schizophrenia, and that she wouldn’t wish it on anybody.

“Without medication, I’d be dead.”

My attempt to downplay it hadn’t gone over well, and looking back it was selfish. I wanted to feel less afraid for my friend, and making her diagnosis smaller was one way to do that. Imagine how she felt and feels.

So how do we talk about mental illness?

Some reframing is important, mostly in regard to the way mental illness was dealt with before. News flash: it wasn’t. You didn’t talk about mental health, a reality I still see in boomers mostly, who refuse to acknowledge that maybe someone who can’t get out of bed and tried to kill themselves isn’t a lazy piece of shit. They might actually have clinical depression. The fact that there is a conversation, a place where you can say, yes, I am bipolar, without being ostracized is a huge win.

But can we exclude the times when mental health issues cross serious lines? Can we limit the characterization to only the people we admire with the illness? Mills Baker had the following to say:

I don’t pretend bipolar disorder is a desirable, quirky eccentricity unfairly maligned; I also feel only mild and IMO appropriate “shame” about it, and I’ve learned a lot from being bipolar…I wouldn’t trade this knowledge for anything, even as I can get quite sad imagining how my life might’ve been different without the disorder. That’s life: complex tradeoffs and attributes (that don’t define us) playing unpredictable roles in what sort of experience we get here on Earth.

I’ve felt this shame myself, but not around mental illness (I don’t have bipolar), which can not be controlled. Mine is around my fundamentalist Christian past, a choice I made. There are things I said and did in those years of my life that I am ashamed about, but as quoted above, I believe it is appropriate shame. I’ve had to reach out to people in my past and apologize, and I believe rightfully so. You don’t get away with telling people who were vulnerable with you that they’re going to hell, even if you do an about face and admit you don’t know shit about the universe later.

I was also raised with alcoholics, something I did not choose. The amount of shame that brought to my childhood is immeasurable. I wore it like a cloak. Would I trade my experiences with extreme religion or an unstable childhood? No, because I think it formed me. I can’t take those things back and see myself here and now. But I’ve spent time that could amount to years, very sad, wondering what could have been had I never stepped foot in a revival meeting, or if the adults in my life hadn’t been so broken. A tradeoff.

How do we write mental illness?

The reason all these thoughts brought me back to The Last House on Needless Street is because of the main character, Ted. He is fat, isolated, strange, with poor hygiene. He is very unstable, a total recluse, the victim of years of abuse by his mother. He has a daughter, Lauren, who comes to visit him some weekends, but aside from her and his cat, he is alone. He drinks too much and suffers from fugue states where he blacks out. He is scary, unpredictable, and seemingly dangerous. He becomes the focus of a young woman’s search for her sister’s abductor after she learns that many children in the area where Ted lives have gone missing.

I’ll pause here.

If you don’t know horror, you might not realize that there are many tropes around mental illness in the genre. Take Edgar Allen Poe’s short story, The Tell-Tale Heart, where an insane man is driven to murder because of the look of an old man’s eye, or Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. In horror, mentally ill people are portrayed as violent, capable of torture and murder.

Can you see the issue with that? It isn’t true that mentally ill people are all violent or scary. Like any trope, it deserves to be turned on its head.

Catriona Ward’s book does just that. Ted, our most obvious suspect for a child murdering serial killer, turns out to have DID, or Dissociative Identity Disorder, known previously as Multiple Personality Disorder. His illness was a trauma response, the result of years of significant abuse at the hands of his stoic, nurse mother. He is a victim of the stigma. Weird, outcasted, ugly and unstable. And yet in the end we feel compassion.

I watched an interview with her, and she explains some of her motivation around why she wrote the book the way she did. She wanted to show a character with a mental illness who was a victim, rather than a perpetrator of whatever horrible thing was happening in the book. I found that moving. Her intentions were pure. The reception, however, has been mixed.

Goodreads had many reviews for The Last House on Needless Street, and one in particular that caught my eye by someone who claimed to have DID. She didn’t appreciate Ted’s character because he was so creepy. To her, the writing reinforced stigmas and assumptions around the disorder. Is this another case of crying out, “I’m not like Kanye! Don’t lump him in with me!”

Maybe. Is it safe to assume that on the spectrum of mental illness, there is a variety of presentation? That not every person with bipolar or DID or schizophrenia is the same? The problem probably lies in the lack of nuance in our talk around anything and everything, including mental illness. We’re all marketing and influencing for the thing that we care about most. When we write though, there has to be diversity. The ugly girl deserves a role. (And I don’t mean the girl who thinks she’s ugly. I mean the real, lived experience of an objectively unattractive woman).

For every ten people crying out, “Hey, I have bipolar, and I would never say anything like Kanye did,” there’s someone else living up to Kanye’s presentation. To me, the problem is in always trying to scale, to market, to find a message that the majority finds palatable. To take what is really an individual, unique experience (mental health), and turn it into a slogan. It can’t be done.

Reframing mental illness is necessary in so much as we acknowledge, listen, understand, and encourage treatment without judgment. The experience and manifestation of it can not be flattened to a point on a graph.

Mills Baker wrote his article (which you should all absolutely read) with a blip of a reference to media. His main issue is with the actual mental health scenes themselves. But media stood out to me, mostly because I’ve been tricked by it. Behind the demand for diverse characters is this: the need for depth, for people who are more than their race, sexuality, gender, etc. Whether publishing houses and film studios are getting that right is up for debate.

What does this mean for our writing? How do we avoid creating characters who follow along that trope of the insane, without resorting to cutesy lies about what it really is? And of course I don’t mean this only in terms of mental health. I mean it in every aspect of character writing. How do we actually breath life and make a character three-dimensional? How do we do that in a world that is insisting we ourselves remain 2D, neatly categorized, unmoved from the paper?

With regard to "Reframing Mental Illness"

Great post.

I'd add to the conversation that it's important to bring in other elements besides the points you've made so well. My experience is that there is also an interactive, social element to this stuff. How people react to others with specific disorders seem to have an impact on people's ability to deal with their mental illness. I have a close friend who had repeated psychotic episodes when she was living in abusive situation and after the situation changed, the episodes stopped.

There're also financial issues too. I knew another who was severely disturbed (I hesitate to state an illness---but I thought schizophrenia if I had to guess) but managed to keep herself together (car, apartment, clothes) simply because she had financial support from her family. Since poverty is inherently hard work, I can only suspect that many of the things that put us off many people with mental illness is the poverty we force them to live in.

As for dissociative personality disorder, I've had the odd short period of conscious dissociation, so I suspect that I have a better chance to understand it than most. What I learn from it is that the fundamentally unitary model of consciousness that is the Ur Philosophy of modern society is simply wrong. We may not 'contain multitudes', but there are several voices and perspectives in each of us.

As for guilt. That too is a burden. I came from a dysfunctional family and had a dysfunctional adolescence and early adulthood---which means I did some things that weren't pretty and haunt me to this day. I like the idea that people are trying grade mental states on a curve instead of pass/fail. But, as you point out, this can go too far. There still failing grades! But having said that, it is really important to cut out the idea that people have some sort of omnipotent intelligence and self-control that allows them to always do the right thing, in every instance of their entire lives. And if they make one mistake they need to be punished for it forever.

Almost nobody wants to accept that we are all flawed and manifest those flaws in a myriad of terrible ways. If you really hold onto that idea and work through the implications, there are a lot of things that people don't want to accept. For example, how about pedophiles, rapists, mass murders, dictators, war criminals, etc? Where do you draw the line when you start to seriously look at the complexity of human behaviour? That's a can of worms that almost no one wants to open---left or right.

This was an excellent, thoughtful piece about such a very difficult subject. 30 years ago I first met an author, who became a friend, who was writing mysteries with a bi-polar protagonist. Excellent mysteries, but her goal was to push back against the idea that people with mental illnesses were all violent, and her motivation was her bi-polar son. Watching that protagonist struggle with the questions of taking medication, what it gave her, what it took from her, was one of the best educations I have ever had in understanding why it is that the people who have subsequently come into my life, who have that particular illness, so often refuse or go off their medication.