If you’re just joining, you may want to check out Part I, Part II, or Part III.

“Would anything happen to the band if she became a cannibal?”

“Yes.”

“What would likely happen?”

“She would kill people.”

-From the trial transcripts of Joseph Fiddler, Fiddler and Stevens, Killing the Shamen

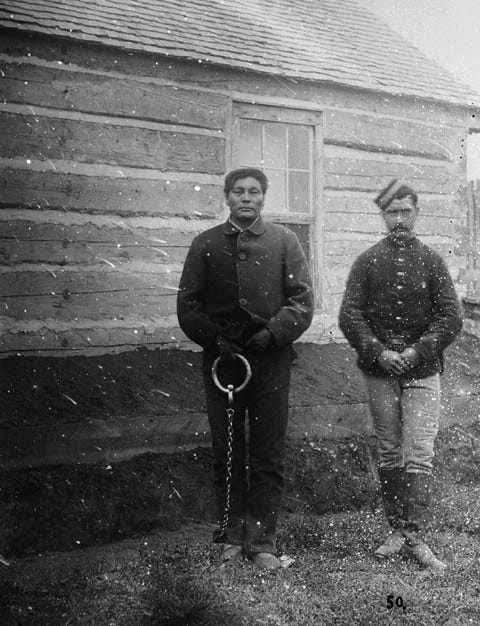

Swift Runner, the Wendigo1

In the spring of 1879, a Cree hunter and trapper named Swift Runner stumbled out of the forest and into a Catholic mission in northern Alberta. The priests went to attend to him, shocked by his disheveled state. He told them that his wife had committed suicide, and the rest of his family, including six children, his mother-in-law and brother, had died of starvation.

The priests looked him over. He wasn’t starving to death despite his claims that he hadn’t been able to find any food during the winter months. He was over six feet tall, a towering man who needed sustenance to survive. How was it that he had escaped the throes of death while each of his family members had died?

They watched him over the coming days. Night after night, Swift Runner would wake up screaming from nightmares. When the priests spoke with other Cree hunters, they found that contrary to Swift Runner’s claims, they had been successful over the winter hunt. They suspected that the circumstances surrounding the deaths of his loved ones was suspicious. When they caught Swift Runner trying to lead a group of children out into the woods, telling them he was going to take them hunting, their fears were confirmed.

The priests were more convinced than ever that his family members hadn’t starved, but had been murdered. They went to the police with their fears. Swift Runner was taken into custody and questioned, but when the police talked to him and tried to convince him to lead them to his winter camp, he refused. It was only when one of them got him drunk that he opened up and offered to lead them to where he and his family had lived in the previous months.

The next day, he led a group of the North West Mounted Police to his camp site. The men emerged out of the woods into a clearing. Bones littered the ground. They were broken open, the marrow sucked from them. A skull was found with a child’s stocking stuffed into the eye socket. Swift Runner walked calmly to another skull, bashed in and larger than the others and said, “This was my wife.”

When asked what had happened, he claimed a bear had killed them all. That lie was put to rest when an officer walked to a pot near the fire pit and took the lid off. Inside, filled to the brim, was human fat. The police arrested him and gathered as much evidence as they could carry. Swift Runner explained to them that he had killed his family, but not because he wanted to. It was because of a wendigo. He had been possessed in the months leading up to their deaths, and despite his best efforts, he could no longer resist the evil spirit’s compulsions.

Over the course of the investigation, authorities learned that Swift Runner was a well-liked and mild mannered man who had worked first for the Hudson’s Bay Company, and then in 1875 as a guide for the same police force that arrested him. He was known among his tribe and the trappers and police that worked with him as a quiet man, a loving husband and father. That is, until he started drinking when he was in his thirties.

A combination of the decimation of the forests and the encroaching Canadian rule over First Nations clans and tribes grated Swift Runner. He resented the settlement of the forests his people had inhabited for thousands of years. With the demands of the fur trade, he and other Cree were having difficulty finding animals, which made it hard to feed his family. As pressures mounted and resources were growing thinner by the year, Swift Runner turned to alcohol.

Swift Runner may have been kind and trustworthy when he was sober, but when he drank he was violent and abusive. A man unhinged who could not be trusted. People were afraid of him and started to avoid him. After years of trading and working for the Hudson’s Bay Company, he was caught stealing furs to trade for whiskey. After that they wanted nothing to do with him.

His life took a definitive turn when he got into a drunken fight with a trader at Fort Saskatchewan. He was arrested and thrown in jail to sober up. After a few days he was released with a warning to stay away from the fort. When he returned to the Cree settlement his family lived on he was angry and withdrawn. It was then that he started hearing voices in his head.

Out of a job and struggling to feed his wife and six children, Swift Runner’s mood darkened. He drank more and his behavior grew unpredictable. He told his family that he was hearing from the spirit world, and that a wendigo was calling to him. His tribe, struggling to hunt the sparse woods around them, decided that he could no longer live there. Under the pressures of basic survival, he was too much of a liability. In the winter of 1878, Swift Runner left and took his family into the woods to set up their own camp.

That winter was hard. Depressed and unmotivated, Swift Runner was watching his family waste away before his very eyes. They had to kill their dogs and eat them to survive. After his oldest son died, the struggling man was pushed over the edge. He was melancholy. He withdrew from his family. He didn’t hunt. He didn’t speak much. Later he would say that he felt inhuman. He felt that he was a wendigo.

His wife, brother, and mother-in-law were still trying to find ways to feed their family. They left to go hunting, leaving one of Swift Runner’s sons behind with him, and taking the other children along. One night, he watched the sleeping boy, and was overcome by thoughts of killing him. He did so brutally, then butchered the body by the fire outside and roasted him. When he was finished eating, he felt satisfied. The wendigo urges subsided. He later told authorities that he smoked by the fire, feeling relief for the first time in months. He decided then that it was time to find the rest of his family.

He followed their trail and found their camp. When he came upon his wife, son, infant daughter, and two oldest daughters, his appearance frightened them. He was disheveled. Something in his eyes wasn’t right.

“Where is your mother? Where is my brother?” he asked his wife.

Seeing that something was wrong, and not believing him when he said their other son had died, she lied to him.

“They died of starvation. It’s only me and the children.”

He feigned belief, but knew that she was trying to deceive him. They all went to sleep that night, but Swift Runner was awakened later by the voice of the wendigo. He shot his wife, killing her before taking an axe to his two oldest daughters. His youngest son and infant daughter were left alive while he butchered their bodies by the fire and prepared the flesh for meat. He told his youngest son to fetch snow in a pot to get water boiling.

Swift Runner ate his wife’s brains while the meat from the others roasted. He brought his son to the fire and ate with him before deciding to kill and eat his infant daughter. When they were finished feasting, he gathered his youngest son, telling him they were going hunting. He wanted to find his mother-in-law and brother.

Their trail wasn’t hard to follow. He found them sleeping, and killed them both in their tents. He set to work butchering them for meat. He and his son carried the meat back to camp, curing some and eating the rest. After a few days, he finally decided they needed to move on. As they traveled, they hunted ducks for food. Eventually, Swift Runner killed his youngest son and ate him as well, his entire family murdered in that sparse winter.

If you followed along in this series, you will know that this is one of the distinctions between wendigo legend and cannibalism for survival. A person overcome by wendigo does not eat human flesh out of pure need. They eat even when other food is available. At the time of the murders, Swift Runner and his family were 25 miles away from supplies. Not only that, but other Cree hunters and trappers in the area successfully hunted animals that winter. Swift Runner was not just starving. He was hungry for human flesh.

On August 6, 1879, Swift Runner was tried for murder and cannibalism. On the jury were a number of Cree members. The evidence against him was overwhelming. He himself had admitted that he had killed his own family and “made beef of them.” His defense: that he had only killed his own family and nobody else’s. It took the jury twenty minutes to find him guilty. He was sentenced to death by hanging and was executed on December 20th, 1879.

Windigo Psychosis

The brutal details of this story were later attributed to windigo psychosis, a psychotic disorder that was first written about by anthropologist Father John M. Cooper in an article titled, “The Cree Witiko Psychosis” in 19332.

A severe culture-bound syndrome occurring among northern Algonquin Indians living in Canada and the northeastern United States. The syndrome is characterized by delusions of becoming possessed by a flesh-eating monster (the windigo) and is manifested in symptoms including depression, violence, a compulsive desire for human flesh, and sometimes actual cannibalism.

-APA Dictionary of Psychology

More followed in his footsteps, with anthropologists writing on the so-called culture-bound psychopathology for decades. The problem was that by the time they started to write on it in the 1930's, 40's, and even on into the 60's, any modern cases of the psychosis had disappeared. It has since been discarded as a hysterical representation of mental illnesses that could be otherwise classified. Anthropologists wrote about it, but many psychiatric professionals wrote it off as unsubstantiated, and some have even argued that it was nothing more than the Algonquian form of a witch-hunt.3

Wendigo is not found in our modern interpretation of mental illness, but we do have examples of modern day cannibalistic compulsion. I can’t help but be reminded as I read these stories of the serial killers that were consumed by a drive to kill and eat people. Jeffrey Dahmer killed and ate his victims, and he is one of many serial killers to describe a feeling of being overtaken by something other than themselves. Killing became an impulse, compulsive, irresistible urge. Something that felt outside of their body. Is he any different than Swift Runner, whether we classify him as windigo or a borderline personality with sadistic tendencies?

Windigos in the modern day would indeed be classified under any number of mental illnesses and personality disorders. We hold them in prisons, sentence them to death in court rooms, watch crime documentaries about them. We fear them. In the forests of Canada, the clans of Jack Fiddler and Swift Runner dealt with insanity, delusion and violent tendencies in the way that survival deemed necessary to them.

Final Thoughts

As modern society and consistent access to food overtook the old ways of the Canadian wilderness, windigo psychosis disappeared along with it. The long rumored and mythical windigo stories passed into the realm of legend. Valuable stories that were used as teaching tools, but lacked any facts at their core.

The stories are certainly that: teaching tools. They serve to turn people back to nature, to conservation, and most importantly, to the care of one another, even in the most desperate of circumstances. Cree beliefs were heavily focused on Manitou the creator and the creatures of the forest. Cannibalism was strictly forbidden, and in many cases would lead to our equivalent of the death penalty. Not because they were tried by a jury of their peers, but because windigo had entered and overtaken the person. Once they ate human flesh, they would never be satisfied with anything else.

But, and this is important, they did not hold windigo as a mythical being as western culture did and does today. They feared it as a real demonic spirit, a creature that stalked when food was scarce and the winter long. Perhaps those spirits are held at bay by the modern world’s marvelous inventions of global farming, trade, and production. Thanks to those advancements, there aren’t many who would starve in the remote forests today. There may not be an opening for such a spirit to sneak in. To possess. To overcome.

On the other hand, the windigo is a greedy spirit. It hungers but is never satisfied. It represents constant consumption and overindulgence. It was, after all, the drive of the fur trade that took the Indians in both the story of Jack Fiddler and Swift Runner to the brink of starvation. In those hard winters, when the bison and beaver were all but eradicated, we see the uptick of murders and cannibalization among the clans in the forest.

The windigo spirit first drives the endless want. The want drives the constant consumption. That overconsumption creates scarcity. And in that scarcity, the windigo stalks and waits. Perhaps we have yet to see that spirit of the old forests because we have lived in eternal summer. The food comes in shipping containers and semi-trucks. Rain or shine, wind and snow, we eat. But one day, maybe soon, the land may stop producing, and the windigo spirit may prove to be more than just a legend after all.

Details surrounding the story of Swift Runner can be found in the book, Swift Runner by Colin Argyle Thomson. I also found a great Canadian podcast on the story here, on Dark Poutine - True Crime and Dark History.

“The Cree Witiko Psychosis,” Primitive Man (now Anthropological Quarterly) 6 (1933): 20–24

I found this dissertation by Louis Marano to be a very convincing argument in favor of windigo psychosis being a circumstantial and non-unique experience in pressured and resource starved societies. Essentially the northern Canadian version of a witch-hunt.